Resources

Browse our full library of in-depth resources and publications

The PacWastePlus programme team is committed to producing meaningful and valuable publications and resources that provides guidance for improving waste management in the Pacific

Search

Composting

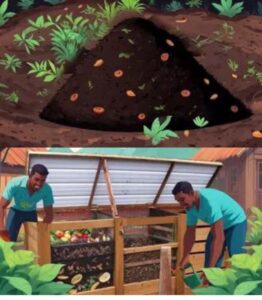

Establishing a compost facility in your community (with subtitles in Kiribati language)

Currently much of the waste going to community dumps is organic materials (40-65%) which, when mixed in a dump with other material like plastics and nappies etc, can cause soil and water pollution, odour, and methane (climate change effects).

Converting this material to compost can benefit communities – by improving soil quality, increasing crop yield, assisting climate resistance, and saving money (replace imported fertilizers).

This animation assists communities to establish a community scale compost program (for communities up to 50 households) – briefly covering topics of:

1. importance of organic materials management

2. how to make a compost bin

3. how to add items: understanding the “carbon / nitrogen ratio”, and ensuring correct balance of air, food and water

4. how to use compost

Organic materials are not a waste – they are a resource!

For more details in establishing a community compost facility please visit the factsheet:

https://pacwasteplus.org/resources/how-do-i-compost-a-guide-for-community-composting/

Available in 5 other languages - Tongan, Chuuk, Pidgin etc...

Composting

Establishing a compost facility in your coomunity (with subtitles Itaukei language)

Currently much of the waste going to community dumps is organic materials (40-65%) which, when mixed in a dump with other material like plastics and nappies etc, can cause soil and water pollution, odour, and methane (climate change effects).

Converting this material to compost can benefit communities – by improving soil quality, increasing crop yield, assisting climate resistance, and saving money (replace imported fertilizers).

This animation assists communities to establish a community scale compost program (for communities up to 50 households) – briefly covering topics of:

1. importance of organic materials management

2. how to make a compost bin

3. how to add items: understanding the “carbon / nitrogen ratio”, and ensuring correct balance of air, food and water

4. how to use compost

Organic materials are not a waste – they are a resource!

For more details in establishing a community compost facility please visit the factsheet:

https://pacwasteplus.org/resources/how-do-i-compost-a-guide-for-community-composting/

Available in 5 other languages - Chuuk, Tongan, Pidgin etc....

Composting

Establishing a compost facility in your community

Currently much of the waste going to community dumps is organic materials (40-65%) which, when mixed in a dump with other material like plastics and nappies etc, can cause soil and water pollution, odour, and methane (climate change effects).

Composting

Establishing a compost facility in your community (with subtitles in Chuuk language)

Currently much of the waste going to community dumps is organic materials (40-65%) which, when mixed in a dump with other material like plastics and nappies etc, can cause soil and water pollution, odour, and methane (climate change effects).

Converting this material to compost can benefit communities – by improving soil quality, increasing crop yield, assisting climate resistance, and saving money (replace imported fertilizers).

This animation assists communities to establish a community scale compost program (for communities up to 50 households) – briefly covering topics of:

1. importance of organic materials management

2. how to make a compost bin

3. how to add items: understanding the “carbon / nitrogen ratio”, and ensuring correct balance of air, food and water

4. how to use compost

Organic materials are not a waste – they are a resource!

For more details in establishing a community compost facility please visit the factsheet: https://www.youtube.com/redirect?event=video_description&redir_token=QUFFLUhqa3lIclZZWi1zM1RCR3JZUlU3NTR5TmJucld1Z3xBQ3Jtc0trbFcxTDZ5TW56SlBvUjQ0TnBsM2h1Q1c0QXY2eDl5VGdKTDhNNEtqeE1HMmFCS0ZIMW1nYmg2LVFUdEd4MUNFQjg4d1VGU1dvZUt3QkRvbUtSYS0yb3pMUkQxZW9SbFZ1R0ZnMEcxZDFaUl9FV2pjOA&q=https%3A%2F%2Fpacwasteplus.org%2Fresources%2Fhow-do-i-compost-a-guide-for-community-composting%2F&v=N-keq2d1Ppw

Available in 5 other languages - Tongan, Chuuk, Pidgin, etc...

General

Organics Composting_Data Collection & Monitoring

The Organics Management and Composting Daily Data Collection Template can be used to track and manage the composting process - recording organic materials diversion and input to a compost facility, and monitoring key factors such as carbon/nitrogen ratios, temperature, maintenance etc.

The Organics Management and Composting Daily Data Collection Template allows compost facility operators to track the composting process and identify issues early, and make adjustments to maintain the quality of the compost. The template can be used by communities operating a small compost facility, or a central facility processing 1 tonne a day or more.

The Organics Management and Composting Daily Data Collection Template can be used in combination with the Composting Standard and other resources on the PacWaste Plus website to guide all aspect of organics management.

Programme Governance Document

PacWastePlus Steering Committee Meeting Report, 2024

The Project Steering Committee is established to guide the development and implementation of the PacWaste Plus Programme, ensuring a fair and reasonable decision-making process for project priorities

and funding allocations. The committee meets on an annual basis to discuss project activity and confirm activity ahead of project closure in June 2025. The 2024 programme Steering Committee Meeting and associated other programme capacity building sessions were held from July 31 – August 2, 2024, in Funafuti, Tuvalu.

School Curriculum

Pacific Waste Curriculum Toolkit

Thinking about our waste, and where it goes once, we have thrown it away, is often the last thing on students’ minds. This toolkit aims to provide teachers across the Pacific with resources and activities that will allow them to increase awareness of the issues surrounding waste generation and disposal, as well as enabling students to plan and implement strategies appropriate to their schools, homes, and communities to reduce the amount of waste going to landfill.

This toolkit has been created for teachers/educators in the Pacific region. It has been designed to complement existing curricula in the region. This curriculum package comprises of the following 9 Units:

1. What is waste?

2. Waste in my country

3. Reducing Waste

4. Waste as a Resource

5. Waste at School

6. E-Waste

7. Waste in our Waterways

8. Waste in the Ocean

9. Advocacy and Action for Change

Each unit comprises several lessons with lesson plans that outline the scope and sequence of lessons. Lessons progress by stages and subject matter. Lessons can be taught in a sequence, or lessons selected to suit your own teaching needs.

This Resource Guide provides an overview of the lessons, resources and activities, subject area, and age-group categories available to you under each unit. The activities provided have been developed with the Pacific teaching and learning context in mind and is specifically designed for each of the 15 participating PacWastePlus programme countries.

https://www.sprep.org/publications/pacific-waste-curriculum-resource-toolkit

Resource Template

Legislation Guidance End-of-Life Vehicle Management in the Pacific

PacWastePlus is assisting Pacific Island Countries to improve the management of End-Of-Life vehicles and End-of-Life Tyres by providing guidelines and technical notes on safe handling and dismantling and options for in-country management of these items. This guideline is to provide a legislative guiding template with a technical drafting note that creates an enabling environment for the effective management of end-of-life vehicles at a scale and technological complexity that is financially viable and suitable for the Pacific Islands.

Guideline

How Do I Compost: A Guide for Community Composting

This guide is intended for communities, groups, or small-scale fruit and vegetable growers in the Pacific who seek to compost small quantities of organic materials (approximately 1-2 wheelbarrows per week) in a shared small-scale composting facility using simple tools and volunteer labour.

Resource Template

Standard Operating Procedure – Bay Composting Organics Processing Facility

This SOP guides the effective composting process, providing supervisors and staff the background and guidance on activities to operate and run a compost facility safely, effectively, and efficiently in the region.

Countries are encouraged to utilise this framework to effectively enhance the operations of their compost facilities.

Guideline

Practitioner’s Guideline on Depollution on End-Of-Life Vehicles: Depollution Guideline

The main objective of this guideline is to provide practitioners in the automotive and waste management industries with a comprehensive and practical resource for executing effective depollution processes. This guideline aims to encompass the entire lifecycle of an end-of-life vehicles (ELVs), from the initial assessment of hazardous components to the final destination of depolluted and hazardous materials.

By outlining step-by-step procedures, safety measures, and disposal protocols, this guideline seeks to minimise environmental contamination and promote the safe handling of hazardous substances. This guide was developed for PacWaste Plus participating countries to address the ELV depollution before being baled and shipped to the designated country where further ELV processing can be done.

The target audience of this guideline are the managers and technicians at the depollution and dismantling site, and other local recycler owner-operators. This guideline does not constitute binding regulation and is developed for advisory purposes alone.

Newsletter Subscription

Would you like to subscribe to our quarterly programme newsletter-The Connection?

We care about the protection of your data. Read our Privacy Policy.

Newsletter Signup

To sign up to our newsletter, enter the information below and we will add you to our mailing list for all future regional and project updates.