Resources

Browse our full library of in-depth resources and publications

The PacWastePlus programme team is committed to producing meaningful and valuable publications and resources that provides guidance for improving waste management in the Pacific

Search

Video Resource

E-waste management in the Pacific

E-Waste (or end of life electrical products), when discarded / disposed outside, pose environmental and health risks. There are easy ways available for safe storage, and end of life product management and recovery. We also recommend choosing quality electrical items to reduce the e-waste generation (as products last longer and are repairable) and choosing environmental sound management of items once it reached its end of life. Watch this short animation to learn more.

Resource Template

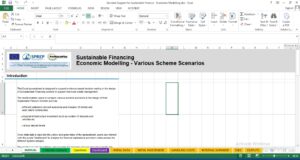

Decision Support for Sustainable Finance – Economic Modelling

This Excel spreadsheet is designed to support evidence-based decision making in the design of a Sustainable Financing scheme to support improved waste management.

The model enables users to compare various scheme scenarios in the design of their Sustainable Finance Scheme such as: different collection network scenarios and inclusion of remote and outer island communities

physical infrastructure investment such as number of deposits and vehicles etc

various deposit levels

Once initial data is input into the yellow tabs of the spreadsheet, users can interact with the purple "Dashboard" to analyse the financial implications and return rates across the different system designs.

The model accounts for inflation, and provides for inclusion of a non-recycling penalty fee.

By evaluating costs, revenues, and material return outcomes, this tool helps stakeholders project scheme performance and determine a financially viable PSS design tailored to their local context.

This model can be used in conjunction with the Calculating Scheme Handing and Administration Fees and Tracking Scheme Performance Model which will help calculate the scheme throughout and further refine scheme costs.

Resource Template

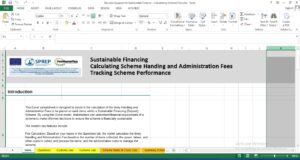

Decision Support for Sustainable Finance – Calculating Scheme Fees

This Excel spreadsheet is designed to assist in the calculation of the likely Handling and Administration Fees to be placed on each items within a Sustainable Financing (Deposit) Scheme. By using this Excel model, stakeholders can understand financial requirements of a scheme to make informed decisions to ensure the scheme is financially sustainable.

The model's key features include:

Fee Calculation: Based on your inputs in the Questions tab, the model calculates the likely Handling and Administration Fee based on the number of items collected, the power, labour, and other costs to collect and process the items, and the administrative costs to manage the scheme.

Labour Calculation: Based on estimated scheme throughput, the model calculates the "man-hours" required to safely collect and process the items

Export Requirements: Based on estimated scheme throughput and size reduction, the model calculates the number of 20ft sea containers that may be required each year to export the items to recycling markets

Performance Tracking: Once your scheme commences, the model provides for you to track collection data and measures scheme performance (against import data). This allows for accurate reporting the identification of areas for improvement.

This model can be used in conjunction with the Economic Modelling spreadsheet which assist users to analyse the financial implications and return rates across the different system designs.

Resource Template

Standard Operating Procedure – Windrow Composting [your facility] Organics Processing Facility

This Framework Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) can be downloaded and customised by operators of medium sized Windrow Compost Facilities, receiving 5-20 tonnes of organic material per week. The SOP can be customised to the local context, and used to guide the effective composting process, providing supervisors and staff the background and guidance on activities to operate and run a Windrow Compost facility safely, effectively, and efficiently. The SOP is split into three sections: • Part 1 – Quick Guide • Part 2 – Stages of Composting • Part 3 – Appendix / Further Reading The SOP is designed to be customised with all areas in yellow designed to prompt an update and tailoring to the local situation.

Resource Template

Bay Composting [your facility] Organics Processing Facility: framework standard operating procedure (SOP)

This Framework Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) can be downloaded and customised by operators of medium sized Bay Compost Facilities, receiving 5-20 tonnes of organic material per week. The SOP can be customised to the local context, and used to guide the effective composting process, providing supervisors and staff the background and guidance on activities to operate and run a Bay Compost facility safely, effectively, and efficiently. The SOP is split into three sections: • Part 1 – Quick Guide • Part 2 – Stages of Composting • Part 3 – Appendix / Further Reading The SOP is designed to be customised with all areas in yellow designed to prompt an update and tailoring to the local situation.

Resource Template

Small Scale Community Bay/Pile Composting [your facility] Organics Processing Facility: framework standard operating procedure (SOP)

This Framework Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) can be downloaded and customised by operators of Small-Scale 3-Bay / Small Pile Composting Facility, receiving less than 100 kg (approximately two wheelbarrows) of organic material per week. The SOP can be customised to the local context, and used to guide the effective operation of a small facility, to ensure the efficient recycling of organic material into compost for soil enrichment. The SOP can be used by households, communities, and small-scale fruit and vegetable growers seeking to establish a compost site, using simple tools and manual labour.

Resource Template

Aerated Pile Composting [your facility] Organics Processing Facility: framework standard operating procedure (SOP)

This Framework Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) can be downloaded and customised by operators of medium sized Aerated Static Pile Compost Facilities, receiving 5-20 tonnes of organic material per week. The SOP can be customised to the local context, and used to guide the effective composting process, providing supervisors and staff the background and guidance on activities to operate and run a Aerated Static Pile Compost facility safely, effectively, and efficiently. The SOP is split into three sections: • Part 1 – Quick Guide • Part 2 – Stages of Composting • Part 3 – Appendix / Further Reading The SOP is designed to be customised with all areas in yellow designed to prompt an update and tailoring to the local situation.

Case Study

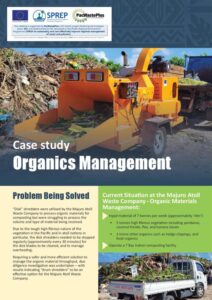

Case Study Organic Management

Due to the tough high fibrous nature of the vegetation in the Pacific and in atoll nations in particular, commonly used “disk shredders” often need to be stopped regularly (approximately every 30 minutes) for the disk blades to be cleared, and to manage overheating.

Seeking safer and more efficient processing , PacWastePlus and the Republic of Marshal Islands procured a “drum shredder” to process their organic material – approximately 7 tonnes per week. This case study describes the performance of the drum shredder, with main findings include:

Power and durability – the drum shredder can handle tougher materials and is less prone to wear and tear.

Faster processing - the rotary drum design allows for continuous and more efficient shredding, which leads to faster processing speeds.

Safer processing - tough high fibrous material does not get “caught up” in blades and therefore does not require staff to reach inside and between the disks

Composting

Establishing a compost facility in your community (with subtitles Vanuatuan languages)

Currently much of the waste going to community dumps is organic materials (40-65%) which, when mixed in a dump with other material like plastics and nappies etc, can cause soil and water pollution, odour, and methane (climate change effects).

Converting this material to compost can benefit communities – by improving soil quality, increasing crop yield, assisting climate resistance, and saving money (replace imported fertilizers).

This animation assists communities to establish a community scale compost program (for communities up to 50 households) – briefly covering topics of:

1. importance of organic materials management

2. how to make a compost bin

3. how to add items: understanding the “carbon / nitrogen ratio”, and ensuring correct balance of air, food and water

4. how to use compost

Organic materials are not a waste – they are a resource!

For more details in establishing a community compost facility please visit the factsheet:

https://pacwasteplus.org/resources/how-do-i-compost-a-guide-for-community-composting/

Available in 5 other languages - Tongan, Chuuk, Pidgin etc...

Composting

Establishing a compost facility in your community (with subtitles in Tuvaluan language)

Currently much of the waste going to community dumps is organic materials (40-65%) which, when mixed in a dump with other material like plastics and nappies etc, can cause soil and water pollution, odour, and methane (climate change effects).

Converting this material to compost can benefit communities – by improving soil quality, increasing crop yield, assisting climate resistance, and saving money (replace imported fertilizers).

This animation assists communities to establish a community scale compost program (for communities up to 50 households) – briefly covering topics of:

1. importance of organic materials management

2. how to make a compost bin

3. how to add items: understanding the “carbon / nitrogen ratio”, and ensuring correct balance of air, food and water

4. how to use compost

Organic materials are not a waste – they are a resource!

For more details in establishing a community compost facility please visit the factsheet:

https://pacwasteplus.org/resources/how-do-i-compost-a-guide-for-community-composting/

Available in 5 other languages - Tongan, Chuuk, Pidgin etc...

Composting

Establishing a compost facility in your community (with subtitles Tongan language)

Currently much of the waste going to community dumps is organic materials (40-65%) which, when mixed in a dump with other material like plastics and nappies etc, can cause soil and water pollution, odour, and methane (climate change effects).

Converting this material to compost can benefit communities – by improving soil quality, increasing crop yield, assisting climate resistance, and saving money (replace imported fertilizers).

This animation assists communities to establish a community scale compost program (for communities up to 50 households) – briefly covering topics of:

1. importance of organic materials management

2. how to make a compost bin

3. how to add items: understanding the “carbon / nitrogen ratio”, and ensuring correct balance of air, food and water

4. how to use compost

Organic materials are not a waste – they are a resource!

For more details in establishing a community compost facility please visit the factsheet:

https://pacwasteplus.org/resources/how-do-i-compost-a-guide-for-community-composting/

Available in 5 other languages - Tongan, Chuuk, Pidgin etc...

Composting

Establishing a compost facility in your community (with subtitles in PNG language)

Currently much of the waste going to community dumps is organic materials (40-65%) which, when mixed in a dump with other material like plastics and nappies etc, can cause soil and water pollution, odour, and methane (climate change effects).

Converting this material to compost can benefit communities – by improving soil quality, increasing crop yield, assisting climate resistance, and saving money (replace imported fertilizers).

This animation assists communities to establish a community scale compost program (for communities up to 50 households) – briefly covering topics of:

1. importance of organic materials management

2. how to make a compost bin

3. how to add items: understanding the “carbon / nitrogen ratio”, and ensuring correct balance of air, food and water

4. how to use compost

Organic materials are not a waste – they are a resource!

For more details in establishing a community compost facility please visit the factsheet:

https://pacwasteplus.org/resources/how-do-i-compost-a-guide-for-community-composting/

Available in 5 other languages - Tongan, Chuuk, Pidgin etc...

Newsletter Subscription

Would you like to subscribe to our quarterly programme newsletter-The Connection?

We care about the protection of your data. Read our Privacy Policy.

Newsletter Signup

To sign up to our newsletter, enter the information below and we will add you to our mailing list for all future regional and project updates.